skipledger

Differential disclosure solution for maintaining and exposing information from evolving, append-only journals / ledgers.

sldg Manual

This is a manual / tutorial about using the sldg tool.

Version 0.5.0

Contents

Introduction

An enterprise typically maintains ledgers that capture organizational activity in relational databases. At minimum, if it’s following standard accounting practices, it maintains these as append-only tables. Ledgers are not just for maintaining monies and balances. For example, a ledger might record items entering and leaving a warehouse.

Ledgers are both public and private. You keep good books, you might pay auditors and accountants to review them, and you might share parts or summaries of them with a select few, or the public.

The goal of sldg then is to make tracking an already private, evolving historical ledger easy and allow a ledger’s owner to later share any slices of the ledger’s rows in unimpeachable, tamper proof packages called morsels.

Configuration

Each ledger is defined by a configuration file. This uses the Java properties format: it can be named whatever. An example best illustrates how the configuration works.

Example Files

Example configuration files (and sample outputs) are available here.

Chinook Sample DB

We’ll be using the chinook sample database for SQLite. This popular sample DB is available for many other database engines also, so if you prefer to follow along using another engine, that should work also.

Here’s a listing of a file generated using sldg’s interactive setup command. More about that command later.. The comment lines have been edited out:

sldg.source.jdbc.url=jdbc\:sqlite\:/Users/babak/play/sqlite_sample/chinook.db

sldg.source.jdbc.driver=org.sqlite.JDBC

sldg.source.jdbc.driver.classpath=../sqlite_sample/sqlite-jdbc-3.36.0.2.jar

sldg.source.query.size=SELECT count(*) FROM invoice_items AS rcount

sldg.source.query.row=SELECT * FROM ( SELECT ROW_NUMBER() OVER (ORDER BY InvoiceLineId ASC) AS row_index, InvoiceLineId, InvoiceId, TrackId, UnitPrice, Quantity FROM invoice_items) AS snap WHERE row_index \= ?

sldg.source.salt.seed=06a38261355760acb05fc1607c61786b828c8e98dc4f4698af9324967a

sldg.hash.table.prefix=invoice_items

sldg.hash.schema.skip=CREATE TABLE invoice_items_sldg ( row_num BIGINT NOT NULL, src_hash CHAR(43) NOT NULL, row_hash CHAR(43) NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (row_num) )

sldg.hash.schema.trail=CREATE TABLE invoice_items_sldg_tr ( trl_id INT NOT NULL, row_num BIGINT NOT NULL, utc BIGINT NOT NULL, mrkl_idx INT NOT NULL, mrkl_cnt INT NOT NULL, chain_len INT NOT NULL, chn_id INT NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (trl_id), FOREIGN KEY (row_num) REFERENCES invoice_items_sldg(row_num), FOREIGN KEY (chn_id) REFERENCES invoice_items_sldg_ch(chn_id) )

sldg.hash.schema.chain=CREATE TABLE invoice_items_sldg_ch ( chn_id INT NOT NULL, n_hash CHAR(43) NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (chn_id) )

We’ll revisit each of these lines in order in the sections below.

Source Connection

The first line (line order doesn’t matter, but setup always writes them out in this order) defines the JDBC URL for connecting to the database

where source table or view lives.

sldg.source.jdbc.url=jdbc\:sqlite\:/Users/babak/play/sqlite_sample/chinook.db

Most of the time the JDBC URL will point to a database living somewhere on the network, not to a local one as in our example. (Note the synatx: colons must be escaped.)

The second line here defines the JDBC driver name used to connect with JDBC URL. Depending on your environment, this information may be redundant (optional) and may be inferrable from the JDBC URL. In most environments, however, you will need to provide it.

sldg.source.jdbc.driver=org.sqlite.JDBC

The third line in our example defines the location of the .jar file where the named JDBC driver may be found. Again, in some environments

this may be redundant (optional), but in most cases you’ll need to set it.

sldg.source.jdbc.driver.classpath=../sqlite_sample/sqlite-jdbc-3.36.0.2.jar

Above, the classpath is defined relative to the location of the configuration file; it may also be set absolutely.

Name/value connection settings (not shown here) are prefixed with sldg.source.info.. For example, readonly=true would be written

as

sldg.source.info.readonly=true

Hash Connection

Per ledger, sldg reads and writes to 3 tables, collectively called a hash ledger. These tables (more about them later) may either live in the same database where source table/view does, or at a separate location. When a “hash connection” is not specified in the configuration fle, then the same connection used to read the source table/view is also used to write to the hash ledger. To keep things simple, our example has the hash ledger live in the same database the source table/view does.

Specifying separate JDBC connection settings for the hash ledger is done the same way as with the source connection,

except that the proptery names prefixed with sldg.source. are now prefixed with sldg.hash..

Source Queries

Two parameters (SQL queries) control the definition of the source ledger:

sldg.source.query.sizedetermines how many rows are in the ledger, andsldg.source.query.rowdetermines what’s in each of those rows.

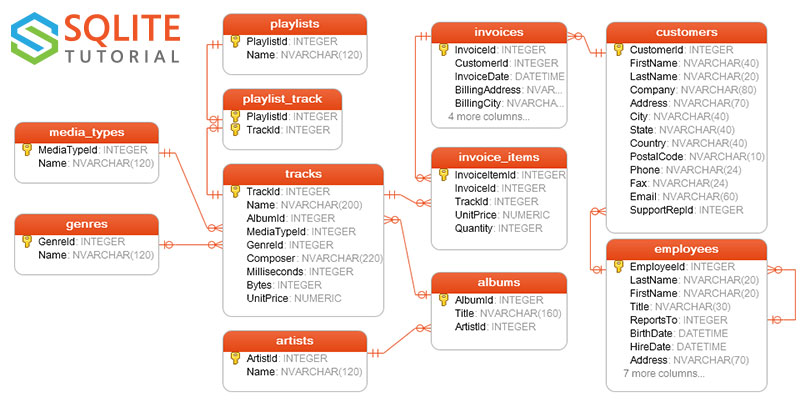

The choice which table or view we use to construct this query is obviously dependent on our existing DB schema. In our example, we are using the table named “invoice_items” as our source ledger. The table’s role in the larger schema is depicted below.

The next 2 lines in the configuration file define the ledger using a view from this table:

sldg.source.query.size=SELECT count(*) FROM invoice_items AS rcount

sldg.source.query.row=SELECT * FROM ( SELECT ROW_NUMBER() OVER (ORDER BY InvoiceLineId ASC) AS row_index, InvoiceLineId, InvoiceId, TrackId, UnitPrice, Quantity FROM invoice_items) AS snap WHERE row_index \= ?

The size query is straight forward: it must be a never-decreasing, non-negative number.

The row query has few constraints on how it must be constucted.

- It takes a single query parameter (marked with a ‘?’) which is the row number. Row numbers range 1 thru size (the value returned by the size query) and have no gaps.

- The query’s result set contains exactly one row. The row’s first column value returned MUST BE the row number (the query parameter).

- The first, the row number column is followed by one or more columns. These may be most any SQL type (large BLOBs can be problematic, but most other types should be okay).

The query here was generated using the sldg’s setup command. That command interacts with the user and takes a list of column values and assumes the first column is a constantly incrementing PRIMARY KEY.

Note the use of the SQL ROW_NUMBER() function here. You might have noticed on inspection that as it turns out, our InvoiceLineId primary key column exactly matches our row number and we might be tempted to define the row number directly in terms of it. That would be a mistake. The reason why is that if at any point, for whatever reason, any row were to be deleted from the invoice_items, then there would be a gap in row numbers. (Granted, nothing is ever supposed to be deleted from an append-only table, but mistakes do happen in the real world, and so we allow for occasional deletes, hopefully near the end of table–for whatever reason.)

Salt Seed

Each ledger also takes a random 32-byte seed value used for salting individual table cell values before they’re hashed. Each table cell value uses a unique salt generated from this seed salt together with the cells row/column coordinates. The purpose of this salting is to prevent anyone guessing what the value of a column must be given the hash of its value (so called rainbow attacks). This seed salt is expressed as 64-digit hexadecimal value.

sldg.source.salt.seed=06a38261355760acb05fc1607c61786b828c8e98dc4f4698af9324967a

(Note in the above example, the seed salt has been truncated to fewer than 64 hex digits–which is invalid, so as to make sure folks don’t somehow end up using the same seed.)

Without this salting, it would not be possible to safely redact column values in morsels.

Secret

Note the random seed salt must be kept secret! There is never a reason to disclose it to anyone: not even an auditor. Failing to do so might leak your ledger’s values. Also, don’t lose it: the ledger’s hashes are useless without this secret.

Hash Ledger

The next name/value pairs in the configuration file define 3 tables that record hashes computed per row from the source table/view:

- Skip table. Maintains the skip ledger structure, one row per source row. This takes the majority of the space overhead for maintaining a ledger with sldg.

- Chain table. Records the Merkle proofs in crumtrails (witness records).

- Trail table. Records crumtrails linking the witnessed hash to that of a row number in the skip ledger. References above 2 tables.

Their table names follow a convention: they share the same prefix which is set by

sldg.hash.table.prefix=invoice_items

in the configuration file. In most cases setting it to the source table name is sensible, but it can be set to something else. The skip-, chain-, and trail

table names are a concatenation of this prefix with the suffixes _sldg, _sldg_ch, and _sldg_tr, respectively.

The next 3 lines (name/value pairs) are in fact optional. sldg’s setup command writes out the default definitions so that if need be they may be overridden.

sldg.hash.schema.skip=CREATE TABLE invoice_items_sldg ( row_num BIGINT NOT NULL, src_hash CHAR(43) NOT NULL, row_hash CHAR(43) NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (row_num) )

sldg.hash.schema.trail=CREATE TABLE invoice_items_sldg_tr ( trl_id INT NOT NULL, row_num BIGINT NOT NULL, utc BIGINT NOT NULL, mrkl_idx INT NOT NULL, mrkl_cnt INT NOT NULL, chain_len INT NOT NULL, chn_id INT NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (trl_id), FOREIGN KEY (row_num) REFERENCES invoice_items_sldg(row_num), FOREIGN KEY (chn_id) REFERENCES invoice_items_sldg_ch(chn_id) )

sldg.hash.schema.chain=CREATE TABLE invoice_items_sldg_ch ( chn_id INT NOT NULL, n_hash CHAR(43) NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY (chn_id) )

This also helps you see the schema. Hopefully, there will be little occassion for overriding these.

Meta Info

You may optionally include a path to a file containing meta information about the ledger. For example, it may be set as follows:

sldg.meta.path=meta/chinook_info.json

This setting directs sldg to look into the meta/ subdirectory (relative to the config file) to find and load the info file. Here’s a chinook_info.json example. (Note this meta info actually corresponds not to the source query setting sldg.source.query.row above, but to the one derived from it in the ledger design section below.)

If the referenced file parses correctly, it can be embedded into morsels created with the morsel command. This information is not validated, nor does it otherwise figure in the operation of the ledger.

Report Template

You may optionally include a path to a file (or directory structure) containing the JSON DSL for generating PDF reports from data in a morsel.

sldg.template.report.path=report

This a new, developer feature, so some capabilities (and tools to help create the DSL) are missing. Here’s a toy example for the ledger described in this example. See the report module for more information.

Commands

The sldg commands are documented in this section. Some details of the command line arguments may be missing below.

The aim here is to complement what’s already self-document in sldg’s own (arguably over-verbose) -help listing.

setup

The setup command walks you thru setting up a config file. It doesn’t actually read or write to the DB, tho it does allow you test whether the connection settings work. It also generates a secure random value for the salt seed. The aim here is to get things started: get the DB connection working, let you inspect what the source query looks like, and fill in the schema design for the ledger.

Example:

$ sldg setup

–new-seed

Often times you may be using another ledger configuration file as a template for a new one. In that case, you’ll need to use a new (secret!) salt seed in the new configuration. Use this command to generate a new secure random seed.

Example:

$ sldg setup --new-seed

88cec878c60fc2c3030cc0a69bffe36f9a60d88c61764090dfcd08d556f79221

This value would appear as

sldg.source.salt.seed=88cec878c60fc2c3030cc0a69bffe36f9a60d88c61764090dfcd08d556f79221

in the ledger configuration file.

Note the commands that follow, all take a configuration file.

create

The create command creates an empty hash ledger on the database. (If the JDBC hash connection is set, then it may be configured to be on a different database than where the source table/view lives.) In order to succeed, the source query must already work. However, so long as you haven’t ledgered any rows yet (i.e. haven’t yet run the update command–more about that below), you can still edit the configuration file’s source query.

Example:

$ sldg confs/chinook.conf create

list

The list command let’s you inspect what sldg see’s at a given row number in the source table/view. For example:

$ sldg confs/chinook.conf list 1-5

update

The update command adds the hashes of x-many new rows from the source ledger to the hash ledger

and then submits a list of hashes from the remaining ledgered [but] unwitnessed rows to the crums.io REST service. Note since the row’s

hashes are linked, only a small subset of the remaining rows need be witnessed.

Example:

$ sldg sldgconf/chinook.conf update 100

100 source rows added

7 crums submitted; 0 crumtrails (witness records) stored

If no number is given, then all the remaining unledgered source rows will be added.

Crumtrails take a few minutes to cure. sldg will retrieved these next time you run another update or the witness command.

status

Prints a summary of the state of the ledger: how many rows hashes have thus far been recorded, a brief history about how it has evolved over time (via witness records called crumtrails), and the ledger’s current hash. The ledger’s current hash, is by definition, the hash of its last row.

Example:

$ sldg sldgconf/chinook.conf status

300 rows recorded in hash ledger

6 crumtrails

1940 rows in source ledger not yet recorded

First crumtrail

row #: 64

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 17:28:04 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635031684864

trail root: b49f9965ae20d567e78fbe793a322293f06e4b632bb67003b086f773c482d0f4

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635031894864&count=-4

Last crumtrail

row #: 300

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 22:32:56 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635049976576

trail root: 8a1457684b393a346b461ac674eb4e7a617d5aaa6033d703af9f79173092f38f

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635050186576&count=-4

ledger state hash (row [300]):

299d0a7a511b772d2eeb3e541b4513c13f0ebaaecffd159dfc101046965526c5

witness

As noted in the update section, rertrieving crumtrails is a 2 step process: you first drop the hash of the object you want witnessed; minutes later you retrieve the crumtrail evidencing when that hash was witnessed.

Invoking update multiple times in succession already automatically picks up crumtrails for previously submitted row hashes. However, if you’re not adding more rows just yet, invoking witness will retrieve the newly cured crumtrails.

Example:

$ sldg sldgconf/chinook.conf witness

7 crums submitted; 2 crumtrails (witness records) stored

Note, on average, sldg saves less than a third of the crumtrails it actually retrieves from the service.

About Crumtrails

The crums.io witness service does not maintain crumtrails indefinitely. Rather, crumtrails are kept in a window of time in which

users are expected to retrieve them before they get purged. This window is designed to be well over a day. Crumtrails, then, employ

a kind of cookie model: the information resides on the client side.

However, crums.io does forever maintain a minimal amount of information about every crumtrail it has ever generated: enough

information to prove the crumtrail really was generated by the service. This information includes the root hash of the Merkle tree

any crumtrail points to, as well as a Merkle proof linking the hash of the previous Merkle tree to its successor and is exposed thru

the REST API.

history

This lists all the crumtrails in the ledger.

Example:

$ sldg sldgconf/chinook.conf history

row #: 64

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 17:28:04 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635031684864

trail root: b49f9965ae20d567e78fbe793a322293f06e4b632bb67003b086f773c482d0f4

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635031894864&count=-4

row #: 96

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 17:28:04 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635031684864

trail root: b49f9965ae20d567e78fbe793a322293f06e4b632bb67003b086f773c482d0f4

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635031894864&count=-4

row #: 128

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 22:20:30 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635049230848

trail root: 87391b3a672000ec84a6ecc073953bee06dd065f64b2e7c63ab0ff2875a3adea

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635049440848&count=-4

row #: 200

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 22:20:30 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635049230848

trail root: 87391b3a672000ec84a6ecc073953bee06dd065f64b2e7c63ab0ff2875a3adea

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635049440848&count=-4

row #: 256

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 22:32:56 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635049976576

trail root: 8a1457684b393a346b461ac674eb4e7a617d5aaa6033d703af9f79173092f38f

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635050186576&count=-4

row #: 300

witnessed: Sat Oct 23 22:32:56 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635049976576

trail root: 8a1457684b393a346b461ac674eb4e7a617d5aaa6033d703af9f79173092f38f

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635050186576&count=-4

row #: 512

witnessed: Sun Oct 24 14:03:09 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635105789184

trail root: bbe772e4549f3b2e43e76153b6f061f9574e0d44c5ac0cd79e687c4141283991

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635105999184&count=-4

row #: 800

witnessed: Sun Oct 24 14:03:09 MDT 2021 UTC: 1635105789440

trail root: bbe772e4549f3b2e43e76153b6f061f9574e0d44c5ac0cd79e687c4141283991

ref URL: https://crums.io/api/list_roots?utc=1635105999440&count=-4

800 ledgered rows

state witnessed and recorded at 8 rows

The trail root here is just shorthand for the “root hash of the tree in the crumtrail’s Merkle proof”. The ref URL is the crums.io

REST URL for looking up past Merkle roots: if you open that URL you should see the trail root value near the top of the returned list. (Note, other REST API methods return the proof connecting the witness tree to the previous

one, however this method was deemed more intuitive from a user perspective.)

morsel

This creates a morsel file. If you don’t specify any row numbers, it just creates a state morsel. For example:

$ sldg sldgconf/chinook.conf morsel -s chinook/

State morsel written to chinook/chinook-state-1460.mrsl

As a convenience, if you don’t explicitly name the morsel file to be created, it generates a hopefully reasonable filename based on the directory it’s saved in.

To include source rows, include their row numbers. You can also redact values by column-number. Like SQL, column-numbers start from 1.

$ sldg sldgconf/chinook.conf morsel 1000-1005 -d 8 -s chinook/

Source morsel (6 rows) written to chinook/chinook-1005-1004-1003-1002-.mrsl

Here the source rows numbered 1000 thru 1005 were also written to the morsel. However, their 8th column

invoices.BillingAddress was redacted.

Inspecting our example file with the mrsl tool yields

$ mrsl chinook/chinook-1005-1004-1003-1002-.mrsl list

[1]

[2]

[4]

[8]

[16]

[32]

[64]

[128]

[256]

[512]

[768]

[896]

[960]

[992]

[1000] S 1000 185 2565 0.99 1 52 Sun Mar 20 00:00:00 MDT 2011 [X] London Un..

[1001] S 1001 186 2571 0.99 1 58 Wed Mar 23 00:00:00 MDT 2011 [X] Delhi Ind..

[1002] S 1002 186 2577 0.99 1 58 Wed Mar 23 00:00:00 MDT 2011 [X] Delhi Ind..

[1003] S 1003 186 2583 0.99 1 58 Wed Mar 23 00:00:00 MDT 2011 [X] Delhi Ind..

[1004] S 1004 186 2589 0.99 1 58 Wed Mar 23 00:00:00 MDT 2011 [X] Delhi Ind..

[1005] S W Mon Nov 29 01:13:53 MST 2021

[1006]

[1008]

[1024]

[1280]

[1408]

[1440]

[1456]

[1460]

28 rows, 1 crumtrail, 6 source-rows.

Redacted column values are marked as ` [X] `. Running a summary on this last morsel, we can see it also contains the hash of the last row–i.e. the hash of the ledger when it contained 1460 rows:

$ mrsl chinook/chinook-1005-1004-1003-1002-.mrsl sum

<chinook-1005-1004-1003-1002-.mrsl>

-- Chinook Invoices --

Rows:

count: 28

# range: lo: 1 hi: 1460

with sources: 6

History:

witnessed: Mon Nov 29 01:13:53 MST 2021 (row 1005)

<1460-2aa9fae8075b36358914fcbe22faa5d35c5416586cd5c9e98ed83aea9975284f>

The file is about 8k:

$ ls -l chinook/chinook-1005-1004-1003-1002-.mrsl

-rw-r--r-- 1 babak staff 8705 Sep 15 13:20 chinook/chinook-1005-1004-1003-1002-.mrsl

It’s more than twice the size of the state morsel we just created:

$ ls -l chinook/chinook-state-1460.mrsl

-rw-r--r-- 1 babak staff 3995 Sep 15 13:14 chinook/chinook-state-1460.mrsl

That’s because state morsels contain little information. Compare its summary:

$ mrsl chinook/chinook-state-1460.mrsl sum

<chinook-state-1460.mrsl>

-- Chinook Invoices --

Rows:

count: 16

# range: lo: 1 hi: 1460

with sources: 0

<1460-2aa9fae8075b36358914fcbe22faa5d35c5416586cd5c9e98ed83aea9975284f>

If we removed the ledger’s meta file from the configuration, it would be even smaller. Since the size of state morsel goes by the logarithm of the number rows in the ledger, this file is compact even if the ledger has millions of rows.

For this reason, a ledger’s state morsel can be used to record or advertise a snapshot of the ledger’s state opaquely. Unlike a straight hash, these snapshots (the morsels) are independently verifiable to be linked to each other.

Embed report template

Report templates are a new developer feature allowing custom branded PDF reports to be independently generated from a report DSL embedded in the morsel file. (See the mrsl report command.)

To embed the report template (referenced in the configuration) into the morsel you’re creating, use the -r option. E.g.

$ sldg sldgconf/chinook.conf morsel 1001-1006 -s chinook/ -r

validate

The validate command recomputes the hashes in the ledger from scratch, starting from row one to the last ledgered row. For larger ledgers (with more than, say, tens of millions of rows) this may be a long running batch job. Regardless, you should periodically validate the ledger to ensure no source rows have inadvertently been modified. The hash ledger is also checked for self consistency. Consistency failures in the hash ledger itself are prominently reported. Unless the hash data is messed with directly, this kind of failure should never happen.

Validation stops on the first, if any, source row encountered whose hash does not match what’s already recorded in the hashledger, and the conflict-row’s number is printed to the console. This should be an abnormal condition. If the conflicting row is near the end of the ledger (i.e. a recent row), it may do to just rollback the ledger’s state to before that row. Otherwise, you will need to look into somehow restoring the conflicting source row to its old state.

Note, if there is one, the conflicting row number is not written anywhere but to the console. (It will not show up the next time you invoke status, for example.)

Startup Validation

It should be noted that sldg performs a mini validation at startup anyway: it validates the both the first row and the last row. The validation of the last row, of course, is only partial: it checks the last source row hash matches what’s recorded and then does a quick consistency check on row’s effective hash.

If validation fails at the first row, sldg assumes it’s a misconfiguration and halts immediately.

The upshot of this check is that if that last source row is at all modified it will be noticed immediately (with an uncermonious warning). Further, should any already-ledgered source row get deleted, that too will almost certainly get picked up at start up. (To pin point which row was deleted, you’ll still need to invoke validate afterward.) What isn’t detect at startup is any changed column value in a “middle” source row.

rollback

The SQL view that models your source ledger is supposed to appear as an operationally append-only table. (Here, operationally append-only means whether by SQL schema constraints, application-engine constraints, or “just how you do things”.) However, this being the real world, mistakes happen.

rollback takes the conflict [row] number reported by validate and rolls back the hash ledger to one less than that row number. sldg first checks that the source row’s hash at the given conflict-number indeed conflcts with that recorded in the hash ledger (the _sldg table, specifically). The user is then warned about the amount of history that will be destroyed and is prompted for confirmation before proceeding to rollback.

Source Ledger (Query) Design

In most cases source columns don’t come from just one table. Typically, you’ll find an append-only table in your existing schema that records the event you intend to capture in the ledger. Your existing schema being already normalized, that table likely references other tables. You can join in any number of suitable columns from these other tables.

For example, in the chinook sample DB above, our source table invoice_items references both the invoices and tracks tables. Rows

in each of those tables in turn reference (thru FOREIGN KEYs) rows in the customers and albums tables, respectively. The more information

you include in the source view, the more each row can stand on its own in terms of the information it conveys. Stitching this information together will typically involve multiple INNER JOINs.

For example, we might stitch in the shipping address for each invoice item this way:

sldg.source.query.row=SELECT * FROM ( SELECT ROW_NUMBER() OVER (ORDER BY InvoiceLineId ASC) AS row_index, InvoiceLineId, invoice_items.InvoiceId, TrackId, UnitPrice, Quantity, invoices.CustomerId, invoices.InvoiceDate, invoices.BillingAddress, invoices.BillingCity, invoices.BillingState, invoices.BillingCountry, invoices.BillingPostalCode, invoices.Total FROM invoice_items INNER JOIN invoices ON invoices.InvoiceId = invoice_items.InvoiceId) AS snap WHERE row_index \= ?

So long as you have not yet invoked update, you can edit the above query in the configuration file and use the list command to confirm sldg sees the query as you intended.

Column Value Immutability

Remember, by including a particular column in the source query, we commit to its value remaining the same forever after.

The considerations can be subtle. If customers can edit their names after their account was created in the chinook customers table, for example,

then the customer’s name cannot be included in the source query; if, on the other hand, names are not editable (not even

for correcting typos) then the customer’s name can be included the source query. (In real world cases, in order to be able

to regenerate their books as they existed on a certain date, existing ledgers never discard a user’s old name–and

one should be able to construct a query that draws in the user’s old name as it existed when the “invoice” was first created.)

As a rule of thumb, aim to minimize using schema-specific key values and/or identifiers. The reason why is to avoid having to commit to a particular backend schema design. (If you change the backend schema, you want to still be able to write an SQL query that generates the existing ledgered rows.)

In the chinnok example, if the albums table contained a global ID column (say an

ISRC code),

then that column would be preferable to use in a join, than say the albums.AlbumId column.